Develop a curiosity-driven workplace

Read Time: 5 mins

Written By:

Donn LeVie, Jr., CFE

The company, guided by savvy leaders, determined that the prospective suppliers employed email encryption services (EES), which many upright organizations use to foster anonymity and security in communications. However, criminal groups can also use EES to conceal their illicit activities and obstruct investigations. And they can link their primary email addresses to EES services to avoid detection. FabricFibre delved deeper and found that two of its suppliers had some suspicious roots. The company gave those firms a wide berth, and probably saved itself a lot of money and grief.

This fictitious story reflects a real concern as reputable organizations conduct TPDD and discover the possible EES red flags among its suppliers.

Third parties can be primary sources of value, but they also can be risky areas for organizations. The steady evolution of technology has led to a necessary evolution of the TPDD process. We conducted research to determine if potential suppliers’ use of EES, and their EES emails as their primary contacts, could be considered red flags (or not) in the context of TPDD activity. This article summarizes the methodology and outcomes of the research and analysis.

A 2019 Gartner study says that 60% of worldwide organizations each work with more than 1,000 suppliers on average — a number that will grow as business ecosystems continue to expand and become more complex. [See “Third Party Risk Management (TPRM),” Gartner.] However, according to the Gartner study, more than 80% of the legal and compliance leaders that participated said they identified third-party risk after initial onboarding “suggesting traditional due diligence methods in risk management policy fail to capture new and evolving risks.”

Gartner’s study says that 73% of the effort of control functions is dedicated to TPDD activities and recertification of counterparties, and 27% of the effort is devoted to identifying risks during relationships. (Investopedia says a counterparty is simply the other side of a trade — a buyer is the counterparty to a seller. See “Counterparty: Definition, Types of Counterparties, and Examples.”)

Organizations now extensively rely on TPDD for investigating and verifying information about third parties — individuals or organizations who interact, for various reasons, with their ecosystems — to prevent risks resulting from professional relationships and transactions. (Third parties aren’t subjects already included in corporate ecosystems, such as employees and members of boards of directors.)

TPDD helps minimize organizations’ and/or individuals’ reputational, financial and/or operational risks. They focus on potential third parties’ transparency, corporate governance structures, profitability, the presence/absence of bad publicity, etc. Organizations aim to analyze corporate structures, financial key performance indicators and reputational standings to help answer questions about a third party such as: Who’s the beneficial owner? Is the third party profitable? Has it been involved in a financial scam? If I sign a contract with this third party, will I incur any risks?

An organization must include the changing global risk scenario as a factor when performing TPDD. The widespread use of shell companies for money laundering and financial fraud — and the digital revolution that enables anonymous remote transactions without the need for geographical proximity — have increased the likelihood a company may encounter risky situations while interacting with third parties. Therefore, you must improve your TPDD process by integrating drivers that address new risks, including analyzing third parties’ official email addresses that they include on their websites and public documents. In the past, it was enough to analyze third parties’ physical addresses. No more. We must scrutinize digital addresses to find potential fraud or risk.

Use publicly accessible “open sources” (free and paid), such as mass media communications, computer-based data, company websites and annual reports, governmental records and academic information to find a third party’s corporate structure and identify the ultimate beneficial owner. You can then discover the entity’s profitability, viability and capitalization plus negative reports, including possible links with criminal organizations. Moreover, you can study the third party’s commitment to ESG (environmental, social and governance) sustainability issues. Your organization then needs to rate the severity of the red flags you discover via open sources, the potential impact on your organization and your risk appetite.

Common email services are vulnerable to hackers. But EES uses end-to-end encryption to protect the content of emails and ensure that only legitimate recipients can access them. EES provides reliable and secure global information infrastructures crucial for businesses and public and private organizations. (Individuals can also buy EES services.)

EES provides reliable and secure global information infrastructures crucial for businesses and public and private organizations. ... However, criminals and terrorists use the benefits of encryption to conceal their illicit activities.

However, criminals and terrorists use the benefits of encryption to conceal their illicit activities. (See “Counter-Terrorism, Ethics and Technology: Emerging Challenges at the Frontiers of Counter-Terrorism,” Adam Henschke, Alastair Reed, Scott Robbins, Seumas Miller, editors, 2021, Springer.)

Bad actors can use EES to obstruct investigations (a phenomenon known as “going dark”) and prevent law enforcement agencies from gathering evidence for trials and dismantling large criminal organizations and terrorist attacks. (See “Shining Light on the ‘Going Dark’ Phenomenon: U.S. Efforts to Overcome the Use of End-to-End Encryption by Islamic State Supporters,” by Ryan Pereira, Harvard Law School National Security Journal, Sept. 3, 2021 and “Hiding Crimes in Cyberspace,” by Dorothy E. Denning and William E. Baugh Jr., Dec. 2, 2010, Taylor & Francis Online.)

Recent studies of illicit markets, criminal organizations, drug traffickers and terrorist groups have found their increasing use of EES, such as Protonmail, to reduce the risk of interception. (See “New Directions in Online Illicit Market Research,” by Thomas J. Holt, Ph.D., International Journal of Criminal Justice, Korean Institute of Criminology, June 2021.)

Anti-mafia prosecutor Giovanni Melillo concurs that organized crime uses EES to mitigate the risk of interception and keep communications confidential. (See “Il procuratore antimafia Giovanni Melillo: ‘Tra mafie e mondo cyber, relazioni profonde’,” by Rosita Rijtano, lavialibera, Feb. 22, 2023.)

The University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland organized the “Mafia and technology” conference, Oct. 17, 2023, which highlighted the criminals’ use of encrypted communications and the new challenges for authorities.

After we considered the unfortunate benefits of EES that criminals use, we decided to conduct a global research study between June 2023 and July 2023 to understand the number and type of organizations adopting encrypted email as their first point of contact and to identify any correlations and/or anomalies in the sample.

We first identified the domains of the most popular EES companies. (See Table 1 below. Note that some of the companies may no longer be active.)

We then used the EES companies’ domains as keywords to search for companies that, according to company registers and corporate websites, have EES emails as primary contacts. Table 2 (below) shows the number of domains of the surveyed organizations. (We carried out the research via open sources, including company and corporate databases with global coverage, so the information we found isn’t comprehensive.)

As shown in Figure 1 (below) the geographical distribution of the sample is extremely uneven. The companies are concentrated in only 30 countries and more than half (66.55%) are located in Brazil. (Russia, Ukraine, Hungary, Estonia and Germany also have a substantial number of organizations, albeit significantly fewer than those in Brazil. For example, Russia, in second place, only counts for 5% of the companies in the sample.)

It appears that potential third-party companies that use encrypted emails as their main contact addresses is certainly a very rare occurrence, i.e., strictly limited to certain geographical areas. Furthermore, comparing the number of organizations surveyed that use encrypted email to the total number of organizations surveyed in the databases consulted, Brazil moves from the top of the ranking to sixth place, preceded in order by Serbia, Georgia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, North Macedonia and Estonia. (See Figure 2 below.)

The organizations that use encrypted email the most, with a few exceptions, are based in countries with a high risk of money laundering and organized crime. (See “AML Country Risk” and “Global Organized Crime Index.”)

To understand the organizational structure of the sampled organizations, i.e., their size in terms of latest available turnovers (which could show shoddy operations), we clustered organizations, where possible, by turnover, turnover costs and number of employees and turnover. (See Table 3 below.)

Table 3 shows:

(Sixty-seven percent of the organizations in the sample were established between 2019 and 2022.)

This analysis shows that the organizations that adopt encrypted email addresses as their primary communication channel are mostly newly established, have very small organizational structures and an annual turnover cost that’s generally placed below 20,000 euros. A small number of employees and a low turnover cost could in some cases indicate precarious financial instability so they’re unable to meet clients’ demands.

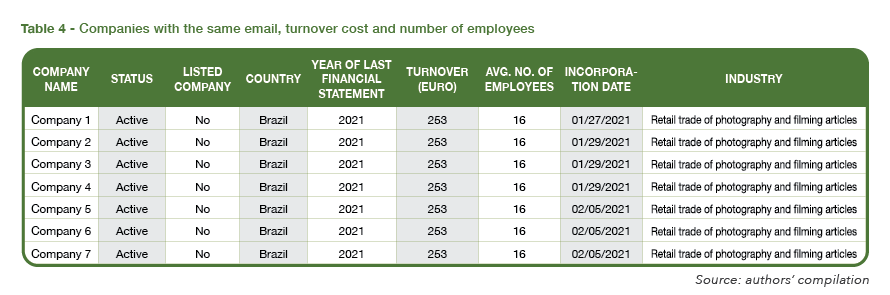

We detected the anomaly that seven Brazilian companies, which all have the same encrypted email address, each show an identical annual turnover cost and average number of employees in 2021. (See Table 4 below.)

The sample analysis also showed that 19 email addresses were repeated for different organizations. Two of them are shared by two companies, both based in Brazil and operating in the retail sector.

To assess how far this could be a risk vector, we examined nine organizations with the same email address. The company name is always the same, except for the initial word, which varies for each company. All nine companies are dealing in the photography and film retail trade. This might suggest that they’re owned by the same group or the same person; however, the managing partner is always different.

Furthermore, seven out of the nine companies (two of the seven companies share the same business address) appear to operate from garages or private houses that don’t have any sign or indication of commercial retail. (See Figure 3 below. We extracted the images from Google Maps after the incorporation dates of the companies.)

Source: The authors identified company headquarters with Google Street View, and images were generated using artificial intelligence.

We analyzed the incidence of the use of EES by sector by recoding product classification codes into 17 macro-categories. (See Table 5 below. The category “Other” includes activities that are more general or less relevant to the analysis, or activities with only one occurrence.)

The trade sector (wholesale and retail) is the most exposed to the use of EES (33% of the entire sample). This is an interesting figure if it’s added to the turnover cost and employee numbers data. According to a 2016 study by the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (see “Organized Crime and the Legal Economy: The Italian Case,” 2016), the characteristics of companies most exposed to the risk of infiltration by organized crime are:

Additionally, the trade sector (wholesale and retail) is considered more exposed to the risk of organized crime infiltrating the legal economy because it facilitates, more than others, illegal activities and money laundering. (See “Mapping the risk of serious and organised crime infiltrating legitimate businesses, Final report,” edited by Shann Hulme, Emma Disley and Emma Louis Blondes, European Union, 2021.)

The widespread use of EES services by organizations operating in the IT sector may be motivated by the attention and sensitivity of these companies on data protection and information security. Information technology can also explain why consultancy firms rank fifth; 16 (39% of the total) consultancy companies specialize in IT.

We believe the following case study represents a good example of how an EES email address as a main contact might be considered a red flag, especially if shared by different companies and tied to other factors or red flags. (We’ve anonymized all identifying elements for confidentiality and privacy.)

The analysis focused on the email r.**********a@protonmail.com, which we found to be the same for three Russian companies in the sample we analyzed.

Based on further research conducted in open sources, this email address is also attributable to “Russian Company 1,” which, in addition to the address with a Proton Mail domain, is also associated with a second email address with the same username but with the extension f**********.pro.

The r.**********a@protonmail.com address would also be traceable to the domain f***********.pro, whose site would no longer be reachable with the extension .pro but only with the extension .click.

We further investigated the websites of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, the Italian Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa (CONSOB) and others, and discovered the domain f**********.pro appears to be traceable to the company “Russian Company 2,” which the Central Bank of the Russian Federation and the National Commission for Companies and the Stock Exchange (CONSOB) placed on blacklists of unauthorized financial operators.

The information we gathered appears to show an association between “Russian Company 1,” present in the sample and “Russian Company 2,” which is involved in irregular conduct on financial markets and suspended by both the Central Bank of the Russian Federation and CONSOB.

In view of our findings, analyzing organizations’ email addresses as TPDD drivers is a good digital indicator — in conjunction with other critical factors — to identify potential risky third parties.

Third parties that use EES services, especially small- and medium-sized organizations, to send or receive confidential documentation to and from counterparties, isn’t a risk itself. In fact, it can be a positive element because it indicates companies’ focus on the security of their information, which could minimize the risk of data breaches.

However, it’s unusual for organizations to use encrypted main email addresses. The choice of an organization to use an encrypted email address as its main contact could be synonymous with a lack of transparency or non-traceability. Treat it as an anomaly that you should assess to possibly find additional red flags.

Continue to religiously conduct third-party due diligence, but assure your methods are contemporary with digital advances.

Antonio Rossi, CFE, is a manager – forensic services with a multinational advisory firm and co-founder and member of the board of the nonprofit association OsintItalia. Contact him at antoniorossi0192@gmail.com.

Lucrezia Tunesi is a threat intelligence expert with years of experience in the energy sector. She is a certified security expert and a certified open source intelligence expert and a member of the Italian Association of Corporate Security Professions (AIPSA) and the nonprofit association Osintitalia. Contact her at tunesi.lucrezia1@gmail.com.

Unlock full access to Fraud Magazine and explore in-depth articles on the latest trends in fraud prevention and detection.

Read Time: 5 mins

Written By:

Donn LeVie, Jr., CFE

Read Time: 18 mins

Written By:

Rasha Kassem, Ph.D., CFE

Read Time: 4 mins

Written By:

Anna Brahce

Read Time: 5 mins

Written By:

Donn LeVie, Jr., CFE

Read Time: 18 mins

Written By:

Rasha Kassem, Ph.D., CFE

Read Time: 4 mins

Written By:

Anna Brahce